“Once it’s out, it’s hard to put the toothpaste back in the tube,” someone said during an interview I was conducting the other day.

He was referring to something business-related, but the moment he said that sentence, I felt my attention drift from his lips and latch onto the ribbon of thoughts unspooling in my head. More words were spoken after that; my phone recorded them, but I didn’t hear them. Instead, I watched as my brain began applying this simple image to a series of scenarios from the past four months. One moment, the toothpaste represented the leak of intangible resources escaping my body and running down an imaginary surface, irremediably lost: time, focus, sleep, energy, drive. The next, it symbolised the snowballing, irreversible effects of certain actions, or words, or sequences of events, which I watched unfold before my very bewildered and disoriented eyes. And even with all this, if I pivoted the camera, I could see myself, hands on a tube, squeezing with all my might.

One hundred and thirty days can be a lot of toothpaste; they can be a lot of life.

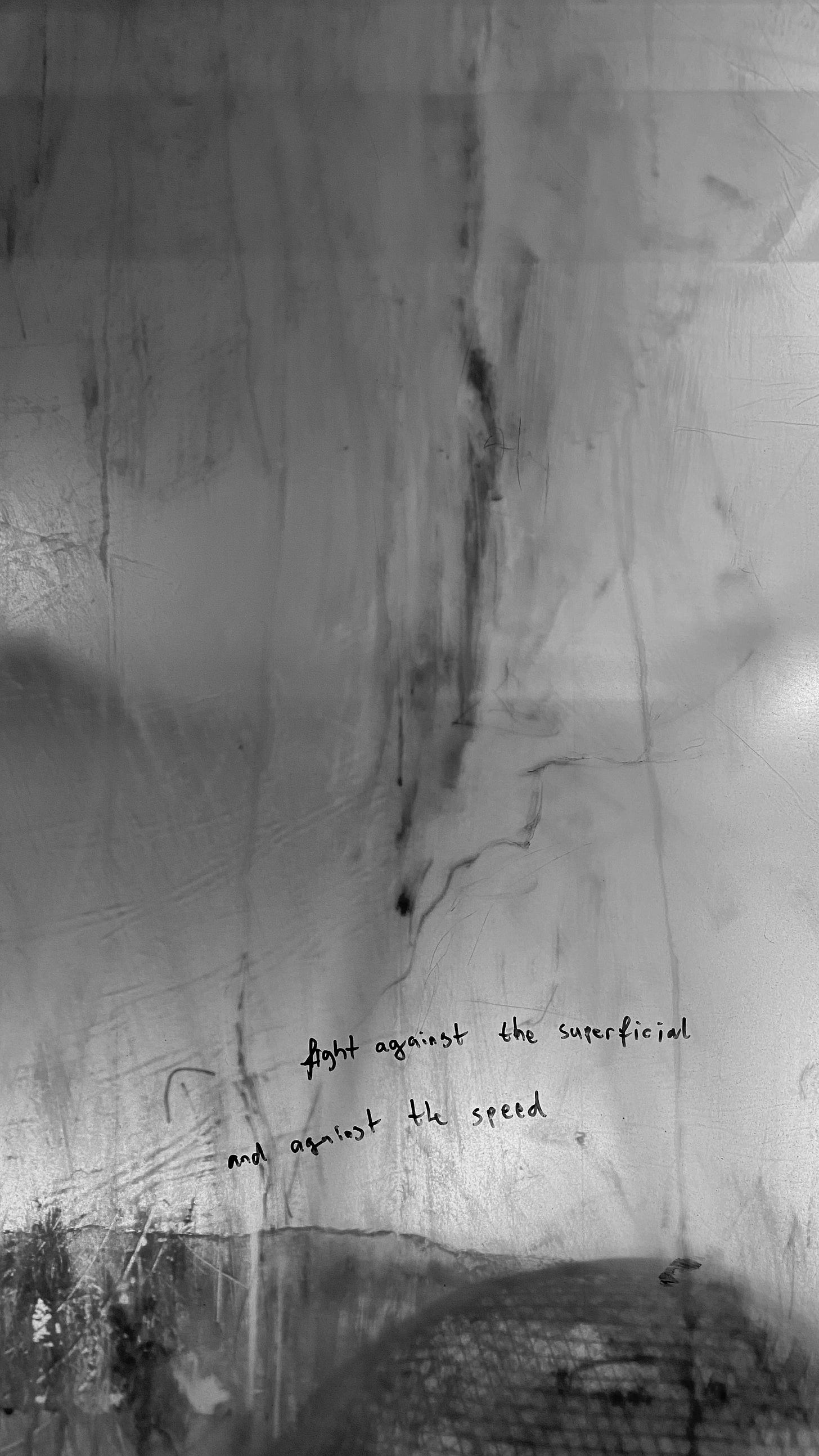

What do I do with all of it now? Pick it up, smear it on a palette, and draw words in savage strokes—sticky, raw, hard to read. And so I write. I have been writing all the words I didn’t write over these months; they pour out of me and inundate everything.

“It’s like finding a one-hundred-euro note on the pavement and leaving it there,” my therapist said back in March, when I told her what had been happening to me, and the choices I though I would make. “These encounters don’t happen often. You might want to pick that note up and see where it takes you. Whatever amount of life comes your way because of it will offer new understandings. Or it could lead to feelings that are unknown to you. Besides, you seem to be craving quiet and chaos in equal measure right now. You might as well do it.”

It was the first time I had spoken to her about my personal life. Usually, we talked about work—about writing and not writing, about impostor syndrome, or preserving one’s attention. This time, I told her, “I’m often under the impression that I build my life as best I can just so I can blow it up with panache right as it starts to peak. Every damn day I wake up, do my fair share, show up to my responsibilities to the best of my abilities, do the work, do the adult things—only so that I can enjoy throwing a Molotov at it all every other year. For no apparent reason, really, other than seeing it glow with sparks. I do it with my career. I do it with my relationships. I do it with everything. It’s exhausting.”

And that’s when she said, “People dismantle what doesn’t serve them, even if they don’t know that that’s the case. In your instance, it might be that you’ve unconsciously been doing what you think you were supposed to do, as opposed to what you wanted to do. So then you reach a boiling point, and just act irrationally after that. Or—or, and this is my guess—it might just be that you like living your life in a way that’s not calculated. Which is not a bad thing, per se; it means you remain somewhat unafraid of discovering what that bigger picture might actually look like for you, if you let it unfold without trying to control it.”

And that’s when I thought, OK. All right, fuck it. Pick up that bill.

I did. I picked it up—it was sitting amongst the ruins of the life I’d just dismantled. And in the end, it definitely bought me a life lesson. The problem now is that there’s no spare change for the rebuilding; that’s entirely on me.

Wasn’t it better to leave it there? I have been wondering, lifting the old stones I blew up one by one, building a new wall around my feelings.

A little over a month ago, a message informed me that I’d been moved from the waiting list to the main list at a gym I’d applied to a year ago. The space was new and came recommended by a few friends who’d had the foresight to join shortly after it opened. Nice people, new machinery, and more light than most places in Venice, they said. So I applied. And waited.

“Are you going to do another long-distance hike this year?” my GP asked after my knee scans came back clear.

“I am. I’m going to do a cammino in Friuli—11 days, 222 kilometres.”

“Fine. You should definitely strengthen the leg muscles and tendons, though,” she said. “At this point, it’s pretty clear the pain is caused by tendinopathy and a lack of muscular support around the joint.”

“I signed up to join the gym a year ago. It appears I’m on a waiting list.”

“Aren’t there other gyms you can join?”

“This one is new and bright. I don’t want to go to a humid den.”

“While you wait, take these collagen supplements,” she added, scribbling something barely legible on a small rectangle of paper and handing it to me, along with verbal instructions on how and when to take them. “Good luck.”

Back home, I returned to the gym’s website to check the application status. Nothing had changed. Maybe they forgot, I thought. Maybe my form got lost. So I filled it out again. And fair enough, a couple of days later, a WhatsApp from an unknown number appeared on my screen. It read: Come whenever you like for your first training session.

Oh, to puff, and hold on tight, and squeeze, and sweat, and swear as a form of catharsis. How beautifully cliché. Truly, the timing couldn’t have been more perfect. I replied: Thank you. I’ll get the paperwork sorted and will come in next week.

“How motivated are you?” the trainer asked during the initial consultation, which was meant to result in a tailored programme.

“I’m extremely motivated,” I said, empowered by the idea of soothing my spleen by tearing my back muscles open.

I told him about the cammino I was about to tackle, about my knees, and he created a programme to support these simple goals. I’ve been training for a little over a month now, and I’ve never felt more ready to start walking.

A friend who’s seen me crawling out of the ruins of the past four months told me it’s all about karmic cycles. A two-year cycle was meant to close in April, she said; it was the universe teaching me a lesson. And I said, “Fine, whatever.”

Then, on that fine day in June, walking home after my first training consultation, I sensed that—just as quickly as that cycle was closing—another one was reopening, this time from twenty years ago. Like a powerful déjà vu, I found myself in the exact emotional landscape I had inhabited as a college student: walking home from the gym—from class, from outings—in a strange state of elation, moving through a positive destruction while also filling up with fluid expansiveness. Now, twenty years later, I find myself feeling similar feelings, halfway between vertigo—like I’m on the verge of something—and grief, all the while inhabiting a body that has luckily remained largely unchanged. I realise I still carry a spirit that remains light, and open. I wear my heart on my sleeve, despite it all. Or perhaps because of it all. The difference, I guess, is that I have more stories to tell. At least, I hope I do.

“You have this really admirable quality of seeking care and affection and love,” another friend from London wrote to me the other day, after one of our river-long phone calls. “Even knowing that heartbreak is a possibility with it. That is not to say it does not hurt. It is brutal, but it is also a consequence of the really beautiful belief that there is love out there for you. That there is a person who could add more to what you have already created,” she added.

I read her words on the screen, and an overwhelming feeling of gratitude filled me to the brim. I let myself cry for a while, holding onto this thought. Outside, a summer rainstorm finally washed away the relentless heat that had accumulated on the stones and pavements of Venice for weeks. The air was cool. I was calm.

At last, the scaffolding came down at the end of June. I decided to celebrate the end of ten months of noise, dust, debris, lack of privacy, intrusions and interference, damaged interiors, and very little light or air entering my windows—with a six-month delay caused by, well, incompetence—in the only way I had wanted to: by washing my sheets and hanging them on the clotheslines so they could swing in the wind and dry in the sun. I used extra fabric softener. I felt in the mood for a splurge.

Not long after this major event came a phone call from my landlady, who announced, in so many words, that it was her intention to sell the flat in January. Therefore, unless I wanted to buy it myself, I’d have to find a new place to live.

“Have you ever considered leaving?” my poor therapist asked me during a different session in which I was venting—literally venting—about the house, and about the struggle of finding a place to live in Venice.

“You know,” I said, “until recently, the idea would never have crossed my mind. Venice is the place where I started anew in my thirties. It’s where I learnt how to be in the world as an uncoupled individual after ten years. It’s where I discovered how much I love to live alone, and the vital importance of good friendships. I didn’t know anyone here, and now, not even five years later, I have this beautiful group of friends—and we all know how rare adult friendships can be. I found my people here, my rhythm, a lifestyle, a perfect balance between urban and village-y. So no, I never thought of leaving—not on my own anyway. I can’t possibly unroot and replant myself somewhere else again. I don’t have the energy for it, not really.

But then again…”

I told her about a conversation I’d had with a friend just the night before. It was an exchange in which we both confessed to each other how trapped we felt, at times, living in this island city—where the atmosphere can be stifling, not very stimulating or diverse, and where there always seems to be a lot to do, but in fact the types of activities on offer all revolve around drinking, going to openings, or attending events related to the Biennale.

“So basically, if you want something else—anything else—you’ve got to do it yourself. Which is great, it’s fantastic: plenty of business opportunities, or chances to get visibility or establish yourself as an authority. But sometimes I just want to sit back and enjoy; I don’t want to always be the one who makes it happen. I want to go to a jazz concert, not organise the jazz concert. Does it make sense?” she said.

I nodded. Then she added, “My biggest fear is that in the next couple of years, for one reason or another, all my favourite people are going to leave, and I’ll be stuck here by myself with this business to run in a city I no longer see as serving me.”

She said all that as we sat on a bench in Sant’Elena, resting our heads after a day at the desk. It was an expansive evening of light and breeze, the water lapping on the pavement at regular intervals, glowing with specks of orange.

“How have you been?” she asked me then.

“Tired. A bit disheartened. A bit emptied,” I said.

We remained quiet for a second, both taking in the weight of our words, of the thoughts they carried.

“Perhaps all it takes is just a change of scenery,” she said. “We need to get out of here more often.”

“A golden cage, this is.”

“And still, I mean. Look at that skyline.”

“I know. Look at it.”

All the while, in the background, Venice shifted from the wintry residues of March to a drizzly spring that lingered until May. Summer exploded at the start of June and is showing some resistance, as though it's here for the long run. The season advanced quietly, marked mostly by the blooming and fading of flowers. The wisteria came first, its clusters always threatened by the next spring rain. Then came the jasmine, filling the air along the edges of the Giardini. Now, for a while, only the oleanders.

In May, the Biennale openings came and went; they felt more subdued than usual. Or perhaps it was just me, being more subdued, constantly lost in thought. A few foundations opened, and a few new exhibitions. The wedding everybody talked about came and went, too. The time of Sagre is upon us: San Francesco, San Piero. Soon, San Giacomo, everybody’s favourite. Then, the Redentore. What are you doing for Redentore? is what people are asking these days.

The days grew longer and longer, and it’s as if the spirit of the city, its very mood, grew more giddy with every minute of daylight it gained. Now, it’s the season of Lido: of those infinite days that almost seem doubled, with one day ending at 6 p.m. and the other beginning right after, with the space–time journey on the vaporetto feeling like a passage to a different dimension—one in which you plunge into salt water and come back anew.

It’s a particular flavour of heartbreak that catches you mid-step as summer explodes around you. It requires a different kind of composure. There’s nowhere to hide; there’s too much to do, too many people to see, too much life to live. But there’s also an inner landscape that doesn’t match the spirit of the season. If you’re not careful, you might find yourself sinking behind dark sunglasses while those around you order a round of gin and tonics, celebrating the beauty of a balmy night. Or walking home at 3 a.m., shattered, not knowing when the shift happened—Wasn’t I enjoying myself just one second ago? you ask yourself in disbelief.

The speed of life in summer is relentless, and beautiful, and all-encompassing. It’s the complete opposite of vita lenta. It’s all there at your fingertips, if you want it.

Do I want it?

I do.

I want the brightness, the frenzy of these days to break into the gloom and crack it open, even if I feel more exposed, more vulnerable than ever. For once, I don’t want solitude. Now I know it was the solitude of winter that led me here.

And still, in solitude I write—and without it, there isn’t much writing. Not here, not elsewhere.

Not much, but some. A long piece on Venice and small-scale climate activism, of which I’m proud. Also, a piece about long-distance walking that serves as a prelude to a bigger project coming soon—the one thing I’m truly looking forward to. I wrote a lot for work: ghost-wrote, copy-wrote, email-wrote. I wrote (and recorded) some voiceovers for a mini-series, and discovered, through this, that I love voicing my own words, and, apparently, I’m good at it. Last week, I wrote a short story that maybe someone will publish, and a personal essay that also, maybe, one day, someone will publish. I wrote three chapters that might never become anything more, and that’s okay, because the process of writing them proved vital, and needed. Mostly, I wrote for myself: an ongoing accumulation of material, of half-digested thoughts and notes that might, one day, become writing.

Someone once said that there’s no writing without life. I suppose, then, that this spring—and this summer now—was, and will be, a time for living, for picking up bills, shattering and rebuilding.

Always lovely writing Valeria so thought provoking.. all I can say is how years pass so quickly and how much I now enjoy ‘Vita Lenta’ and wished I had found more time to ‘just be’ than always ‘doing’ and to be as comfortable in my skin then as I do now, perhaps the wisdom of ageing and a greater sense of the preciousness of time .. anyway I ramble, so tread gently and life will show you the way. 🙏

As always, I enjoyed reading this so much, Valeria, and I wish from the bottom of my heart that one day - not too far away - your stories will get published.